Social innovation is a process to test and mainstream successful new responses to social issues. In this guide we will outlines the innovation process that underpins social innovation and then a practical guide to the social innovation process followed by some practical comments on providing the necessary infrastructure to ensure social innovation is available to all communities.

Innovation can be understood as a step-forward development in an existing thing, activity, process, framework or policy. Once the relevant phenomenon has been implemented and then mainstreamed (general acceptance of the innovation and its wide-range usage) it ceases to be innovative. Thus, innovation relates to a short-term phenomenon. That is not to say that an organisation cannot continue to innovate on a regular basis but it requires a constant flow of innovative steps, one after the other. Social innovation relates to innovation within the social sphere. Social innovation is of course not new, every social project or process we have now had to be created, tested and developed before it became the mainstream phenomenon that we know today. What is innovative about ‘social innovation’ is the fact that it is taking learning from technological and industrial development, including design thinking and applying it to social issues.

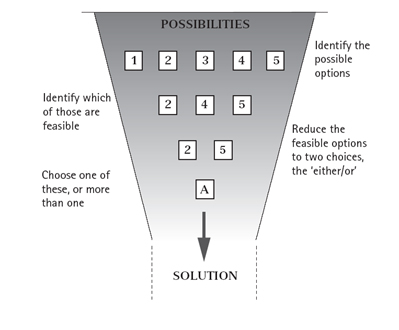

The innovation process has been understood as an innovation ‘funnel’ (Adair, 2004, 33) such as the one outlined below. It starts with taking a question, examining all the possible options usually through a process of market research and then ideation, then assessing which might be most feasible by developing a matrix, bringing the feasible options down to 2 or 3 and then prototyping these until the best new option is arrived at. It is similar to the process outlined in the Stanford Design School process which initiated Design Thinking. Design thinking means designing things and processes from the perspective of the end user and creating processes and things are as intuitive to use as possible. So, start general and then define and redefine until the best solution is deducted.

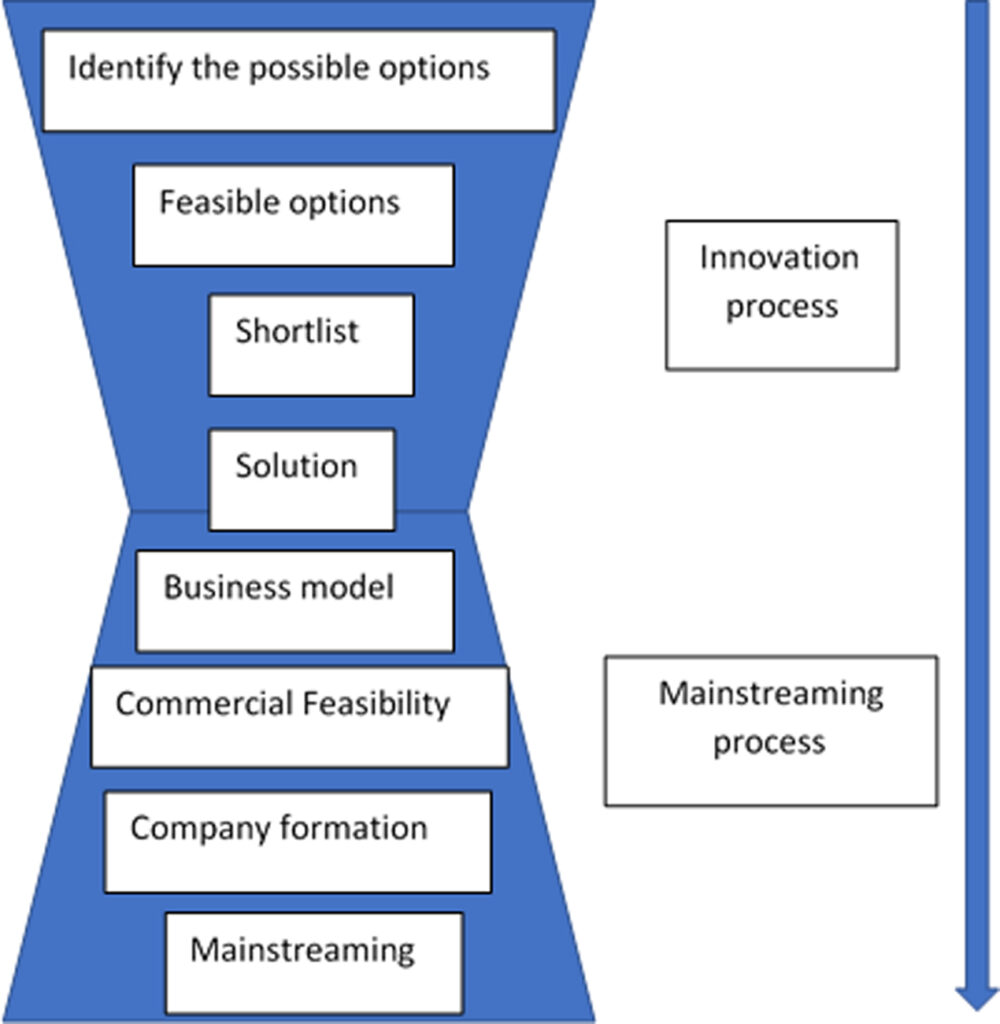

However, it must be remembered that this is only half of the process. Once an innovative solution is deducted it must be implemented. In a commercial situation then this would be described as ‘commercialisation’ but in the social sphere it is described as ‘mainstreaming’. I have outlined the broader process in Figure 2.

Fig.2 reminds us that the point of innovation is not to create a really ‘cool’ new solution but rather to create a solution that solves a problem for many people in practice. Thus, a key question at the ‘shortlist’ stage is to assess which solutions are not only feasible but also ‘commercially’ deliverable or can be ‘mainstreamed’ into social practice. That is not to say that creative destruction is important but whatever solution is arrived at must be implementable.

Towards a process of social innovation

If social innovation is not new then can we develop a social innovation process based upon learning from existing projects in Ireland? Fig.3 gives an outline of such a process developed from personal observation of several socially innovative projects. The aim is to outline how a social project/solution can be developed in practice.

We are not being prescriptive here; this is developed from a general sense of learning from a number of previous projects. In effect, social innovation can be broken down into a 4-step process:

Identification Phase: at this stage someone identifies a serious social issue that is of import to them. It may be a single individual or a group of like-minded people but there are initiators which can be understood as the social innovator(s). The initiators develop a common understanding of the social issue and they raise awareness. They attract other like-minded people and build a core of key stakeholders. If these core stakeholders can develop a plausible solution to the issue and can attract enough support from public and private funders and policy makers then the project can move to the next phase. If they cannot, then the project will become a pressure group raising attention but with no solution.

Pilot Phase: this is where the project has a plausible solution and this is tested in real life. It is not necessary in this phase for a new organisation to be established, the pilot project can be housed within existing organisations or social-innovation hub. It is important that all stages of the pilot is measured and recorded so that the veracity of piloted model can be evaluated. In this stage new methodologies can be tested (design think for example), new processes can be attempted and a ‘trial and error’ method can be applied.

Evaluation Phase: this is the phase in which the veracity of the model being piloted is tested. The social innovators need to be honest and realistic at this phase and ensure any personal bias is taken out of the conversation so as to evaluate the outcomes of the testing. There are broadly only 3 outcomes possible here:

- The pilot project worked. The issue was short-term in nature and the solution solved the problem. The problem no longer exists and thus no further action is required

- The pilot project failed. The learning as to why it did not work needs to be gleaned and the learning mainstreamed to prevent others doing the same again

- The project worked and can be mainstreamed. Thus, a mainstreaming model needs to be adopted to bring the project forward.

Mainstreaming Phase: this is where the pilot project is turned into a longer-term solution. This usually requires the establishment of a new organisation, corporate governance, staffing and agreed method of working. It should become obvious from the evaluation phase as to the appropriate mainstreaming model to be utilised but broadly there are 5 possible models:

- Social enterprise model: a new social enterprise is established to bring the project forward. This solution works best when there is a stream of income raised from paying customers. If there are no paying customers then this model is not appropriate. A social enterprise uses a funding mix of trading income, grants and other sources of income. In the early days grants may be the majority source of income (the public sector pays the social enterprise to provide a good or service to specific client groups), however, over time the trading income should become a bigger percentage of total income. Without a traded income then there is no social enterprise.

- Community-development model: this is the more traditional community group. Usually funded through public sources as a way of addressing local social issues and traditional fundraising. Many community-development groups supplement grants with a range of ‘raised-income strategies’ and some provide services for money such as community centres running coffee shops or crèches. This does not make them a social enterprise. A social enterprise uses its trading income to meet its social aims whereas the community centre is using it purely to fill a gap in its core funding.

- Advocacy Model: another mainstreaming model is an organisation that represents a community of interest and looks after the interests of people who are strong enough to represent themselves. Many have their roots in social movements and others have their roots in faith-based organisations.

- Intermediate-labour market (ILM) model: this is a resource available to the other categories. In Ireland we have a tradition of giving community and voluntary organisations people to deliver services, usually the unemployed, rather than giving them tendered contracts (money). Over time we have used a variety of these schemes such as Community Employment (CE), TUS or the Full-time Job Initiative (JI). Many social enterprises, community groups and advocacy groups have set up CE Projects and used TUS to staff their organisation.

- Other models: there are other forms of organisation that can be used but the above represents the majority of projects.

Having tested the innovative model in the pilot phase, it should be obvious as to which mainstreaming model is appropriate. This may be by process of elimination. If there is no traded income then the social enterprise model is probably not the right one. The key message is this, use the appropriate model for the solution. Do not try and ‘horn shoe’ a solution into the wrong model as it will not work. There also needs to be recognition that there is no ‘one size fits all’ solution to social problems, social enterprise is not the ‘silver bullet’ to solve all social ills.

So to summarise, social innovation relates to short-term phenomenon in addressing social issues. Before any solution is mainstreamed, it should be tested. Broadly, there is a 4-step social innovation process that many successful projects have followed. Only proven solutions should be mainstreamed. There are a range of potential models that can be used but it is appropriate to find the model that best fits the solution (not necessarily the social problem). It also follows that different mainstreaming models need different types and levels of support; social enterprises need a different range and type of support compared to a community-development group or an advocacy group or ILM. Community-development, advocacy and ILM models have long-term models of best practice and are well studied. The social enterprise model is the least understood and has the shortest track record from a mainstream policy perspective.

Some practical policy implications

The following key points should be taken into account when developing any social innovation process:

- Focus on the social issue not the mechanics of delivering it. Social innovation, social entrepreneurship and social enterprises are a means to an end, not an end in themselves. The objective is to use these mechanisms to identify a real social problem and solve it. Getting too focused on the mechanics is a mistake, focus on the social issue

- Assist most new social innovative projects to follow a social innovation process such as outlined earlier.

- No new projects should be supported without being tested and piloted

- Measurement is important so that proper evaluation is enabled. There is no such thing as a mistake in a pilot project only lessons that need to be learned and ensure that things that do not work are not repeated

- An infrastructure around social innovation does exist but social innovations hubs, new philanthropic platforms and a focus on targeting resources on new social challenges in the community is needed. The government does have a role in facilitating this process as the sector is itself not strong enough to achieve critical mass on its own

- Within academia, the existing third-level programmes on social innovation and social entrepreneurship should be continued. However, more effort to include social innovation, social entrepreneurship into the second-level education system and ideally into the higher first-level education system is needed. These programmes need to be imported from external service providers as it is unreasonable to expect first- and second–level teachers to have the skills and understanding necessary to deliver such content-specific programmes

Funding Master works with clients to develop, write and submit funding applications. The opinions set out here belong to the author(s), they constitute opinion and nothing is intended to constitute advice. The blog is authored by Funding Master’s founder and CEO, Dr. Ken Germaine. Please view his profile and please connect with him at his LInkedin profile here. Please contact us directly here if you have any questions on our work or this article. More information on our website here.

Pingback: Resources from Funding Master - Funding Master - Funding Grants